Listen to a radio segment on Ag Ventures Alliance

–by Liz Morrison

A farm cooperative and a high tech company are joining forces to make corn stover a more nutritious cattle feed.

Ag Ventures Alliance Cooperative and Cellulose Sciences International (CSI) plan to commercialize a new process that unlocks the carbohydrates in biomass, improving digestibility. In April, the two companies formed Stover Ventures, which will bring CSI’s patented feed treatment to market.

The new enterprise would offer farmers another source of revenue from their cornfields, says Becky Philipp, AURI project manager. Dairy and beef producers would gain an alternative feedstuff that could be substituted for some corn. The venture could also create new jobs in corn stover harvesting and processing.

AURI is helping the start-up with technical analysis, livestock feeding trials and quality assurance.

Looking for opportunities

Ag Ventures Alliance (AgVA) is a 400-member cooperative based in Mason City, Iowa. Most of the members are farmers from southern Minnesota and northern Iowa. The group, founded in 1998, starts new businesses that add value to farm commodities, says Brad Saeger of Willmar, Minnesota, who is leading the Stover Ventures commercialization effort.

Ag Ventures Alliance (AgVA) is a 400-member cooperative based in Mason City, Iowa. Most of the members are farmers from southern Minnesota and northern Iowa. The group, founded in 1998, starts new businesses that add value to farm commodities, says Brad Saeger of Willmar, Minnesota, who is leading the Stover Ventures commercialization effort.

AgVA focuses on the early phases of business creation—identifying good opportunities and working on organization, financing, marketing and start-up. The goal is to provide new investment opportunities for co-op members, Saeger says.

Farmer-members are especially interested in ideas for adding value to abundant corn stover—the stalks, leaves and cobs left in the field after the grain is harvested.

In corn following corn rotation fields in southern Minnesota and northern Iowa, it’s a challenge to manage ever-increasing mounds of corn residue. In today’s high-yielding environments, corn stover production often “exceeds the minimum amount needed to maintain soil health,” Saeger says.

Removing some corn residue can be an agronomic advantage, says AURI coproducts scientist Al Doering, who is also a farmer. Soil warms up faster in the spring, disease pressure drops, and there is often times a reduced fertilizer and tillage requirement.

Corn stover processing opportunities include cellulosic ethanol and other fuels, chemicals and livestock feed. Biofuel and chemical ventures require huge capital investments: a commercial cellulosic ethanol plant, for example, is a $600 million undertaking, Saeger says. “We wanted to find something with a lower entry cost that could still add value to corn stover.”

That search led AgVA to Cellulose Sciences International, a small technology company based in Madison, Wisconsin.

Breaking down biomass

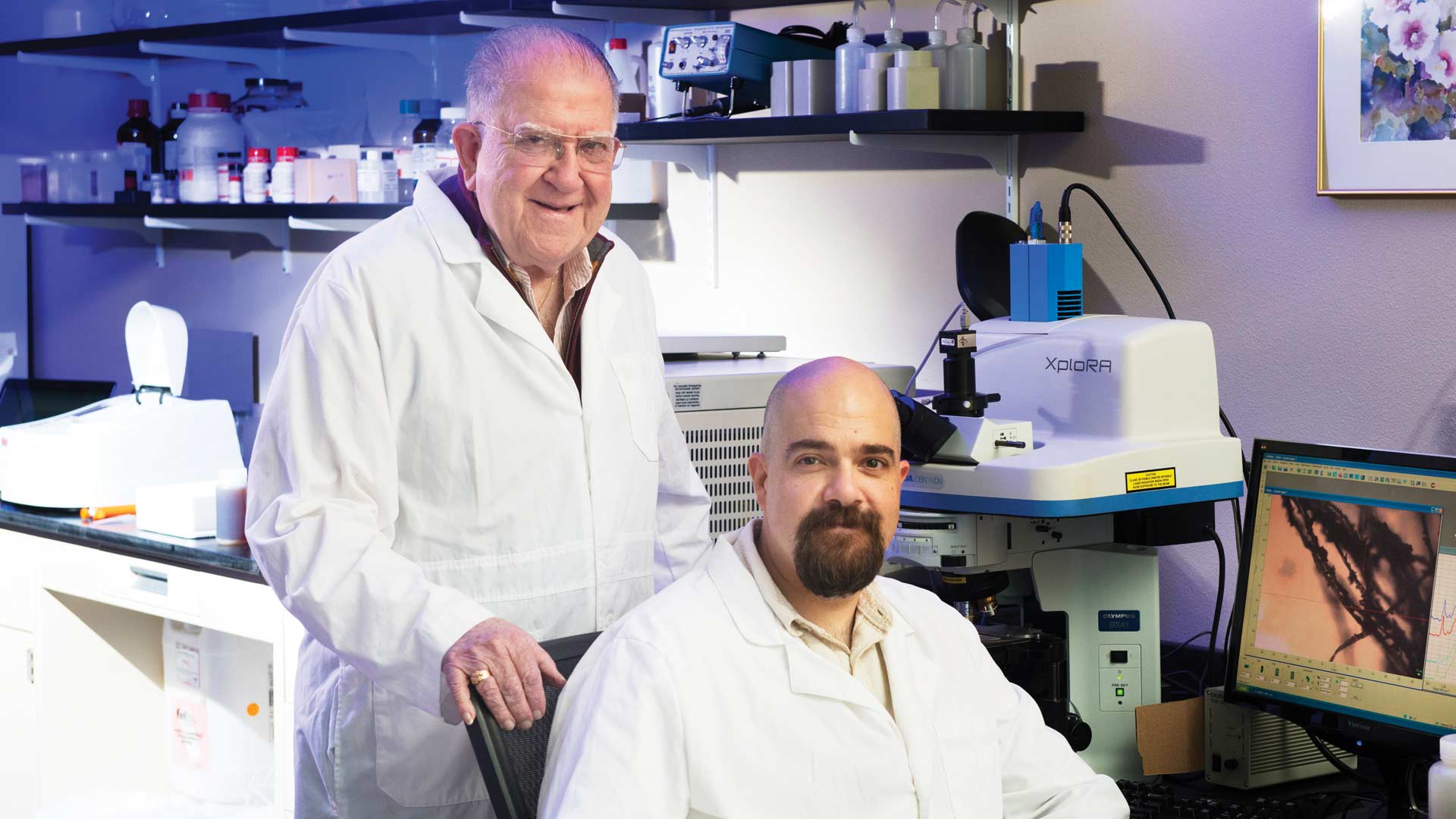

CSI was founded in 2007 by chemist and veteran cellulose researcher Rajai Atalla, a retired scientist with the U.S. Forest Service’s Forest Products Laboratory.

Atalla invented a process that opens up the complex chains of molecules in lignocellulosic biomass making them nanoporous, releasing the valuable carbohydrates bound up in plant fibers. The treatment not only boosts the nutritional value of corn stover, but also speeds up digestion, he says.

In 2013, Atalla made a presentation on the technology at the Midwest Innovation Summit, which caught the attention of Ag Ventures Alliance. The concept “was easy for growers to understand,” Saeger says, “with a low start-up cost, and limited risk to deploy in the short term.”

Efficient, a good fit

AURI helped AgVA fund laboratory evaluations of the CSI process and comparisons with several rival biomass treatments.

The CSI treatment looked like the best choice for AgVA, Saeger says. It uses a mixture of common chemicals—sodium hydroxide, ethanol and water—to release the nutritious sugars in chopped corn stover. Unlike other treatments, CSI’s process does not require high temperatures or pressure, Atalla says. The process, which takes about an hour, produces 1,700 pounds of feed per ton of corn stover, an 85% yield. Nearly all of the processing chemicals can be recovered and reused, pushing down the cost.

“The CSI process looks very promising,” Doering says. “It’s an efficient way to obtain a very good feed product.”

In addition to digestible feed, the CSI treatment also yields two specialty chemicals ferulic acid and para-coumaric acid—potent antioxidants that have high value as food, pharmaceutical and cosmetic additives. These compounds could be worth as much as the feed itself, Saeger says.

The CSI process has other advantages for AgVA, Saeger adds. It’s well-suited to small, centralized plants that would handle about 100,000 tons of corn stover a year, collected from a 20- or 30-mile radius. A plant that size would cost about $14 million to build, he estimates. Saeger estimates that processing will add $50 to $100 per ton to the value of corn residue.

The AgVA venture is also well-timed to take advantage of innovations in corn stover harvesting and handling, Saeger says. These advances are being driven by the cellulosic ethanol industry, which is working with farmers and custom harvesters on efficient, sustainable stover collection methods. That expertise will also benefit farmers who want to supply corn residue to Stover Ventures, Saeger says.

Moving forward

This summer, Stover Ventures produced its first batch of treated corn residue at the USDA Forest Service forest products pilot plant in Madison. Feeding trials at the University of Wisconsin will evaluate the treated stover’s nutritional and economic performance in dairy cow rations.

This summer, Stover Ventures produced its first batch of treated corn residue at the USDA Forest Service forest products pilot plant in Madison. Feeding trials at the University of Wisconsin will evaluate the treated stover’s nutritional and economic performance in dairy cow rations.

Earlier studies at Iowa State University concluded that alkali-treated corn stover and distillers grains could replace up to 20% of corn in cattle rations—without lowering growth. Preliminary cost estimates suggest that the treated feed could be price competitive whenever corn prices approach $4 per bushel, Doering says.

If feeding trial results are favorable, Stover Ventures will identify potential sites for its first processing plant. Several counties in southern Minnesota are strong candidates, Saeger says, offering high corn yields and proximity to large cattle populations.

AgVA has committed $500,000 in seed money to launch Stover Ventures. If all goes well, commercial production could begin as early as 2017, Saeger says. He adds: “The treated corn stover project is one of the single best opportunities for a cooperative-style business we have encountered since the early ethanol years.”

Investing in Minnesota value-added agriculture

Ag Ventures Alliance Cooperative and its members have invested in many value-added agribusinesses in Minnesota and Iowa. Profits from these investments are used to fund new business development. Some of the Minnesota-based companies that Ag Ventures Alliance has taken a stake in:

- Golden Oval Eggs, Renville, processes eggs;

- Minnesota Soybean Processors, Brewster, manufactures soybean meal and biodiesel fuel;

- Feed Logic, Willmar, makes robotic livestock feeding systems;

- Once Innovations, Plymouth, produces confinement barn lighting technology.

AURI and Stover Ventures

Idea to reality: Ag Ventures Alliance (AgVA)—a cooperative made up of farmers from Iowa and Minnesota—was looking for ways to add value to corn stover.

AURI’s role: AURI helped the cooperative evaluate a new biomass treatment developed by Cellulose Sciences International (CSI). The treatment makes corn stover more nutritious, increasing its feed value.

Outcomes: In spring 2015, AgVA and CSI formed Stover Ventures to commercialize CSI’s corn stover feed treatment. The company will produce its first batch of treated corn stover feed this summer. Dairy cow feeding trials also begin in summer 2015 at the University of Wisconsin.

Partners: USDA Rural Cooperative Development Program

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (943.4KB) | Embed