By AURI

Per capita consumer demand for wheat products is trending lower in the United States. In part, this shift is a result of an emergence of health-related concerns like non-celiac gluten sensitivity and irritable bowel syndrome. These digestibility issues have prompted many Americans to remove wheat from their diets.

For the wheat growers, bakers and processors, this trend has significant ramifications. When consumers buy less bread, bagels and cookies, demand falls and can often result in lower wheat prices, and less revenue for bakeries as they sell fewer goods. When the price of wheat drops, farmers look for crops that can provide a higher return per acre, including staple crops like corn and soybeans.

In response to this trend, the Agricultural Utilization Research Institute engaged with two coalitions to study options to reduce wheat digestibility concerns. Combined, this research has the potential to catalyze the creation of new products and processes that will positively impact the wheat industry value chain. These projects involved researchers from the University of Minnesota (UMN) and the University of Alberta, the Minnesota Wheat Research and Promotion Council and Back When Foods, a bakery in Crookston, Minn.

These projects tackled two related questions: Are wheat digestibility issues a result of unintended outcomes from wheat breeding programs and/or the change in dough and baking processing that reduced fermentation steps? If so, can different varieties and processing techniques make wheat easier to digest?

While both projects investigated options to improve wheat digestibility by looking at the fermentation process to make bread and other wheat products, UMN researchers also looked at wheat grown today in the U.S. The projects investigated options to improve wheat digestibility by looking at wheat varieties grown historically and today, and the fermentation process to make bread and other wheat products. In both projects, researchers focused on two components found in wheat thought to trigger some of the health issues associated with wheat digestibility: Fermentable sugars (fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols or FOODMAPS) and amylase-trypsin inhibitors (ATI).

Specifically, UMN researchers investigated the level of ATI and FODMAPs present in current and past Minnesota wheat varieties, as well as their anti-nutrient levels, and the effects of fermentation on FODMAP and ATI levels utilizing a sourdough process. [2] The central question to their report was, are wheat digestibility issues addressable through a combination of selecting the right wheat variety and/or alternative processing, such as sourdough fermentation, to substantially reduce the ATI and FODMAP levels in finished products?

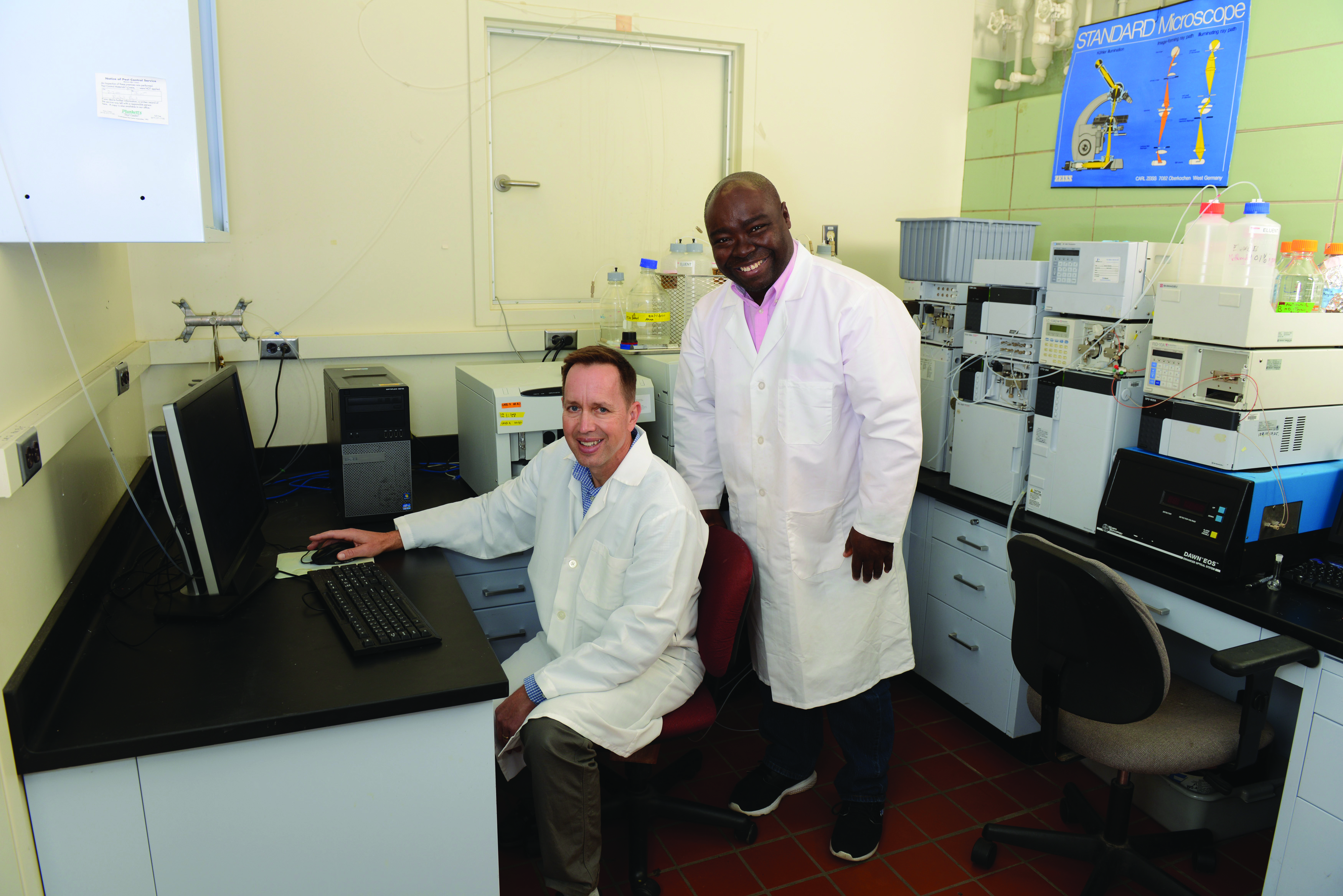

Dr. George Annor, a professor in the Department of Food Science and Nutrition, and Dr. Jim Anderson, a professor in the Department of Agronomy and Plant Genetics, characterized the FODMAPs and ATI across ancient, heritage and modern spring wheat varieties curated by the University of Minnesota wheat breeding program, going back to the late 19th Century. A total of 220 whole grain wheat samples were analyzed for levels of FODMAPs and ATI Researchers extracted DNA and genotyped samples using genotyping-by-sequencing. Researchers used the resulting genetic markers to find associations with genes influencing FODMAP and ATI content.

Dr. Michael Gänzle, a professor in the Department of Agricultural, Food and Nutritional Science at the University of Alberta, focused his research on developing fermentation technologies to reduced levels of unfavorable components in wheat and improve tolerance of wheat products.

Conclusions

Results from genetic mapping did not show any genomic region responsible for a large portion of the genetic variation for these traits. Rather, many genes of minor effect were found to be responsible for most of the variations for ATI and FODMAPs. Both traits, however, should be amenable to selection using conventional breeding methods and genomic prediction. Additionally, the analysis did not indicate any significant increasing trend of FODMAP and ATI levels in varieties from the late 19th into the early 21st century that could explain the increased digestibility issues.

Additionally, wheat samples showed significant variation in FODMAP and ATI levels across a diverse panel of wheat varieties. The wheat samples were grouped according to FODMAP and ATI levels for the fermentation phase of the research, which examined the effects of sourdough fermentation on the levels of FODMAPS and ATI.

“The most interesting part of this research for growers forms the basis of how we can reduce FODMAPs and ATI levels through

breeding,” Annor said. “We believe that if we can continue to screen more samples, we can put our hands on the exact things responsible for the increase in FODMAPs and produce wheat that is low in ATI.”

Dr. Anderson said that it is clear from the research that the length of the fermentation process in wheat production plays a larger role in digestibility issues. He believes there is a market for bread products produced with a longer fermentation period.

“For the consumer, the interesting part of this research is, you may not have a gluten sensitivity. It very likely could be the FODMAPs and the ATIs that are causing these issues, not the protein of the wheat,” Dr. Anderson said.

AURI and the Minnesota Wheat Research and Promotion Council also partnered with Dr. Michael Gänzle on a second project. Dr. Gänzle studied sourdough bread as a possible solution to digestibility issues because the longer fermentation process used in sourdough bread making significantly reduces FODMAPs.2 His research will be published later this year.

“In the past few years, I have talked to many bakers who use sourdough and tell me that their customers can tolerate their bread better. As more consumers start to learn about the positive health effects of sourdough, I think it will spread through the industry. It will take another five years until the American baking industry is using sourdough bread as default process,” Gänzle predicted.

We are shifting back to where we were in the early 20th Century in terms of fermentation process.”

The work AURI is doing to facilitate more research into wheat digestibility is exciting and very much needed, said Charlie Vogel, the executive director of the Minnesota Wheat Research and Promotion Council. Finding new markets for wheat grown in Minnesota is critical to the future health of the industry.

There are about 800 wheat growers in Minnesota. Most of the crop grown in the state is exported.

Vogel said if it is possible to improve the perception of wheat among consumers, there will be many benefits. Minnesota farmers can grow and sell more wheat domestically. Further, when demand for wheat increases, more of the crop will be planted which will directly improve soil health in the state, he said. AURI is also looking into process verification tools that could assure consumers of properly fermented wheat sourdough products with lower fructans and ATI.

“We need to be proactive, and to look ahead to develop these markets. To do that requires us to be nimble and work with other partners to explore these niche areas that will over time become mainstream markets,” Vogel said. “For our group, we are often focused on what is happening right now, so it is very valuable to have partners like AURI to collaborate with on projects like these that are looking forward to new markets and new opportunities.”

Brian LaPlante is the owner of Back When Foods, a sourdough bakery in Crookston, Minn., that is scheduled to open in 2022. He said this research on fermentation process, FODMAPs and ATI is critical to the health of the baking industry and to his own business plans. He has worked with AURI for many years.

“The shift to gluten free diets is really clobbering our industry,” he said. “The spring wheat used in baking is only about 25 percent of the wheat grown in the United States. Pretty soon all wheat produced is going to be spoken for by the large millers and bakeries. We need to create more demand and more markets. To do that we need to turn around the perception that wheat is bad for you. If we can do that, we can encourage farmers to grow more wheat and to be paid more for it.”

There is a clear example in the craft beer industry for how the wheat industry can change from the bottom up, LaPlante said. When small, independent brewers started to make beer with better ingredients and a better production process, consumers took notice. Soon, larger breweries imitated that model.

“Once the large wheat processors take a look at this research and understand the ramifications, they can shift to using a wheat that is lower in ATIs and a longer fermentation process to reduce some of the anti- nutrients from the beginning of the process,” he said. “Right now, it is the smaller independents that are out front on this, but I think the bigger companies will follow.”

LaPlante said AURI’s contribution to this field is invaluable. The organization is an expert product manager and facilitator of large-scale projects like this one, he said.

“It is not easy for an individual like me to connect the many players for this type of research, but AURI can lead a project like this all the way from helping secure a grant from the Minnesota Department of Agriculture, to putting together the right partners, to answering the questions that come up along the way. They are a perfect partner to work with,” he said. Project Manager Becky Philipp and Business Development Director Harold Stanislawski are working on both projects for AURI. Philipp said partnerships like these are central to AURI’s core mission of advancing value-added agriculture.

“This project has so much potential. Everyone knows someone affected by wheat digestibility issues. Plus, if we can help get people to eat more wheat again, it will help the growers and bakers financially. This is really meaningful work,” Philipp said.

The wheat research highlights how AURI can perform the role of a convener and new business accelerator, Stanislawski said.

“There are a lot of products that can be made using the techniques studied in this research. Bread, pasta, cookies, crackers, you name it,” he said. “AURI can help advance ideas like this into commercial products and use our networking channels to get this information in front of consumers.

[2] Funded by the Alberta Wheat Commission, Saskatchewan Wheat Development Commission, Minnesota Wheat Research & Promotion Council and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.