A plucky little start-up company in Afton, Minn. is manufacturing natural red food dye, extracted from a new variety of purple corn grown in southwest Minnesota.

Suntava is selling its trademarked Sayela colorant to food and beverage makers. Sayela is derived from Suntava Purple Corn, a hybrid developed by Red Rock Genetics, an independent corn genetics company in Lamberton, Minn. The high-value niche crop is raised by farmer-members of Meadowland Cooperative in Lamberton.

Suntava and its collaborators exemplify “green industry” trends — crop diversity, health-promoting foods, high-tech research, product development — that will propel job growth in Minnesota agriculture in the coming decades.

Green trends are explored in a new AURI report, “Minnesota Food Production Sector: Growing Green Jobs,” prepared at the request of the Minnesota Legislature. The study looks at green-job opportunities in Minnesota’s diverse food industry, says Teresa Spaeth, AURI executive director. It lays out some of the challenges to job creation and suggests ways that “Minnesota can support high-quality job growth and entrepreneurship in the food production sector,” Spaeth says.

Green jobs are usually associated with renewable energy, says Minnesota State Representative Al Juhnke of Willmar, agriculture finance committee chair and an AURI board member. Yet, “agriculture is the original green industry. There’s a lot of opportunity in agriculture for value-added green job growth. And a good number of these jobs could be in rural Minnesota.”

Market drives growth

Consumers are driving green-job growth in Minnesota agriculture, says AURI project director Kate Paris, who led the report’s research team.

“Sustainability is clearly not a fad,” the report says, but “will, in fact, change food production at every stage of the supply chain — including on the farm.”

At the farm level, demand will rise for a greater variety of local and “naturally-grown” products, says report author Carol Russell of Russell Herder, a Minnesota market research firm. That could lead to more jobs for certified organic producers and truck farmers who serve nearby urban markets. Sustainable agriculture educators, organic certification consultants, horticultural experts and other production support jobs could follow.

Local and regional food distributors will be needed to gather and sell locally-grown foods to wholesale and food service outlets. Farmers markets, on-farm stores and local marketing cooperatives could generate new direct-marketing jobs, too.

Demand for local specialty products, such as artisan cheeses, wine, beer and organic poultry and meat could add processing jobs in rural Minnesota. New retail merchandising techniques will let shoppers trace food products all the way back to the farm and even compare the sustainability of competing products.

Assuring safety

Food safety is another major trend that will spur green ag jobs, Paris says. “Consumer concerns about food health and safety are shaping the industry at every level,” the report says. “Consumers and regulators alike are sharpening focus on how food is grown, processed and produced.”

This will expand the need for jobs and businesses that ensure a safe food supply. For example: companies to track food through the supply chain, technologies to measure food freshness or contamination, hazard analysis experts, food-safety inspectors and trainers, regulatory compliance officers, quality control specialists.

Food-safety jobs will also emerge in high-tech fields such as bioinformation systems, genomics, systems biology and nanotechnology, says Amy Johnson of BioBusiness Alliance of Minnesota. These fields “may not seem to be related to the food industry,” she says, “but they truly are.” She sees “tremendous potential for those businesses to be created within Minnesota,” a technology leader. “There is a definite concentration of skill sets here.”

Innovation

Food processing innovations will also generate green jobs, Carol Russell says. A good example is the rising popularity of “functional foods,” which offer health benefits. Minnesota could become a leader in this sector, “thanks to its powerful combination of research capability, food-processing prowess and production diversity,” she says.

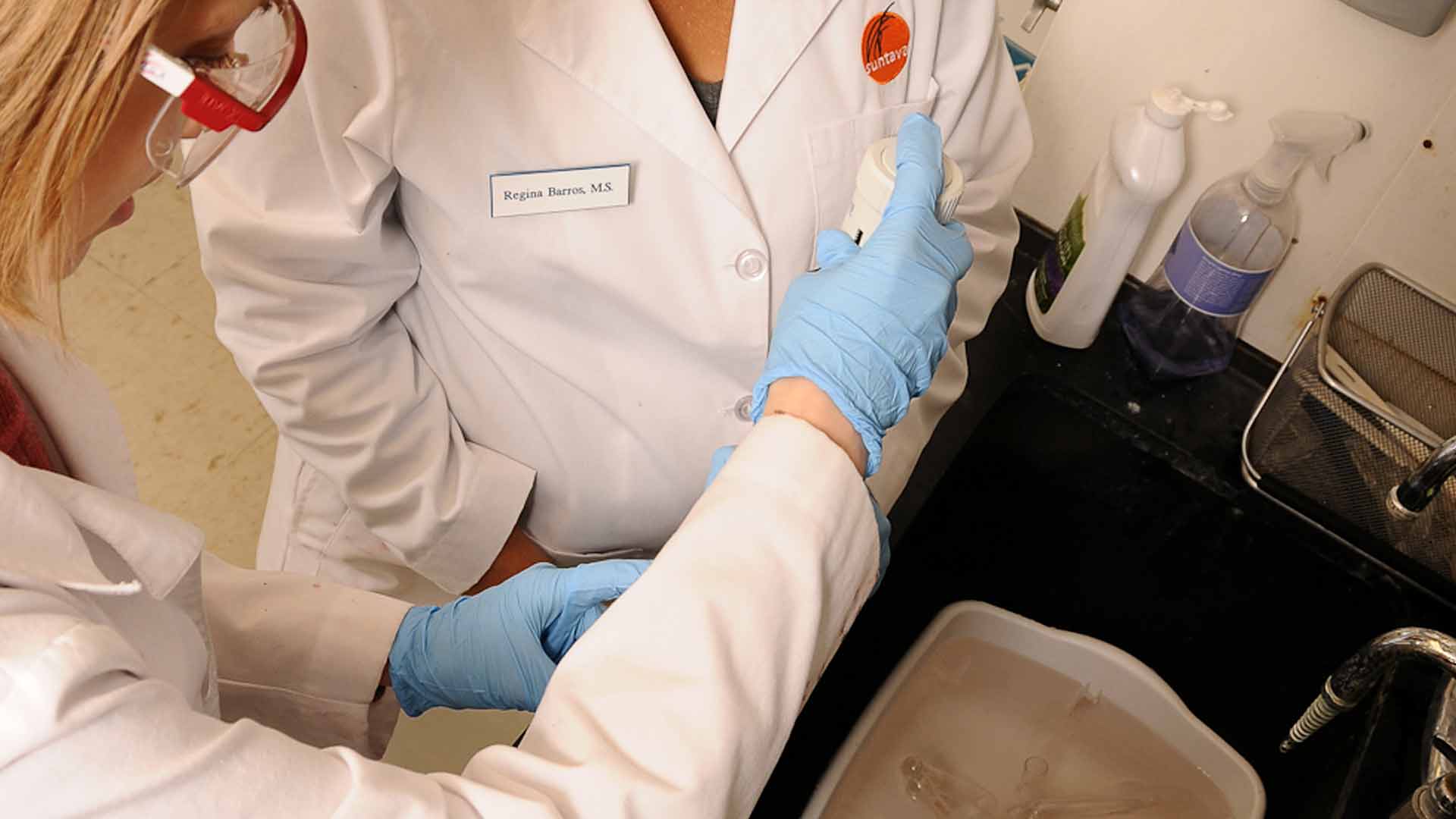

Large Minnesota food processors such as Hormel, General Mills and Land O’ Lakes — and their suppliers — are all pouring resources into functional food research and development, says AURI food scientist Charan Wadhawan. The same is true of small Minnesota companies such as Suntava, which is developing natural food color. Food science advances will also offer opportunities for Minnesota farmers to grow specialty crops, like red corn, for pharmaceutical or functional food uses, Russell says.

Animal agriculture at risk?

Amidst all this potential job growth, one of Minnesota agriculture’s most important job sources may be at risk, Paris says.

Livestock production and processing, which generates more than 100,000 jobs and contributes $11 billion to Minnesota’s economy, faces “significant external threats,” the report says. Increased regulation, public fears about manure management and animal welfare, and local land use conflicts could all weigh on Minnesota’s livestock sector. “Misunderstandings about animal agriculture could have a dramatic impact on not only livestock production in the state, but also the grain producers and food processors that rely on this agricultural sector,” the report says.

Yet animal agriculture offers one of Minnesota’s best opportunities for job growth and economic development, says Kevin Paap, Minnesota Farm Bureau president. “A 400-head dairy generates more jobs than a 4,000-acre crop farm. It also has an impact on grain farmers for feed demand, veterinary services and other enterprises throughout the community, which creates even greater job growth.”

Unfortunately, the livestock industry has not “done a good job of telling our story,” says State Representative Rod Hamilton, a Mountain Lake, Minn. farmer. “We are often combating fallacies … Everyone involved needs to help educate people.”

Brain drain

There are other threats to green-job growth in agriculture.

One of the most vexing is the “rural brain drain,” Russell says. When educated, talented young people leave small farming communities, they take with them the skills and energy that propel innovation, entrepreneurship and prosperity, she says.

Other threats to green-job expansion include weakened demand for food and commodities, volatile crop and energy prices, red ink in the livestock sector, and burdensome or patchwork regulation, the report says. Food sector start-ups and small businesses are stymied by limited access to capital and land, the high price of health and liability insurance, and steep costs for certification and food safety compliance.

Job refocus

Still, there are many steps that can be taken to help Minnesota agriculture respond to emerging green trends, the report says.

Foremost is education — training a workforce to meet the needs of the green economy, Juhnke says. Educators and professionals will be needed in food science, plant genetics, biofuel production, waste utilization, ag software development and business management, to name just a few of the fields that will see green-job growth.

It’s important to recognize that the green economy may not produce a significant net increase in Minnesota ag jobs, Russell says. “It may be more about job refocusing” — not more jobs, but different jobs.

The long-term trend in both production agriculture and processing is more output with less labor, the report notes. Employment on Minnesota farms is expected to be flat through 2016, while employment in Minnesota’s dairy, produce and beverage processing sectors is predicted to decline. Meat and poultry processing employment is expected to increase about 4 percent.

In production agriculture, the green economy will likely prompt a shift to more support jobs, such as agronomy, engineering and precision agriculture services, the report says. In food processing, there could be a shift from manufacturing to jobs in research and development, biotechnology, waste recycling and energy conservation. Almost half of the top 50 U.S. food processors, for example, have sustainability initiatives, such as lowering greenhouse gas emissions and using more renewable energy.

Today, agriculture and food production accounts for one-fifth of Minnesota’s economic activity and generates more than 350,000 jobs. “Our state is very strong in agriculture and it’s easy to take it for granted,” Paris says. Agriculture is “part of what drives the economic health of our state,” she says. “We can use it as a launching pad for further growth.”

“It’s important we grow awareness for this industry,” Juhnke says. “It’s more than just growing and processing — agriculture is economic development.”

To read the report, go to www.auri.org