–by Dan Lemke

Most Americans don’t get enough fiber in their diets. If research into an innovative new technology bears out, an underutilized dairy ingredient could soon provide a hidden, healthy fiber boost.

An emerging research project at the Midwest Dairy Foods Research Center at the University of Minnesota (U of M), and funded in part by AURI and the Midwest Dairy Association, successfully polymerized lactose, a component of dairy whey, into an oligosaccharide, a prebiotic dietary fiber that feeds the beneficial bacteria in the digestive system.

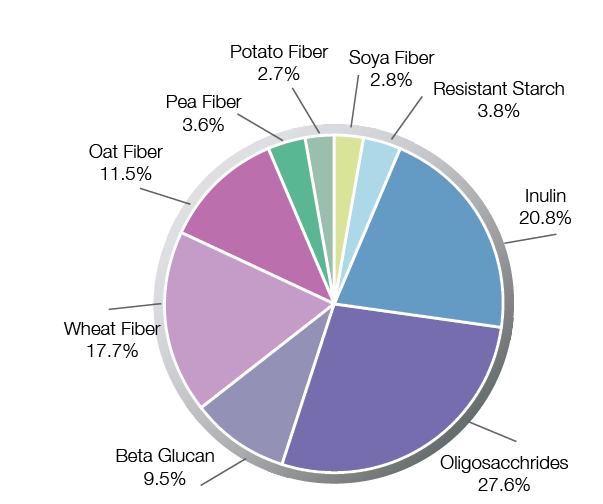

Oligosaccharides have been shown in food to enhance digestive health, benefit the immune system, help with blood sugar control and aid in mineral absorption. These dietary fibers are ideal for food formulations because they easily dissolve and typically have little impact on flavor or texture. Fiber can also partially replace sugar, fat and calories, which makes it compatible with functional foods that deliver on health benefits.

The novel, continuous-flow process tested at the U of M yielded polymerized lactose, called polylactose. It’s an ingredient that has immense potential as a fiber source for the food and beverage industry because many food products ranging from breakfast cereals to yogurt are enhanced to boost their fiber content.

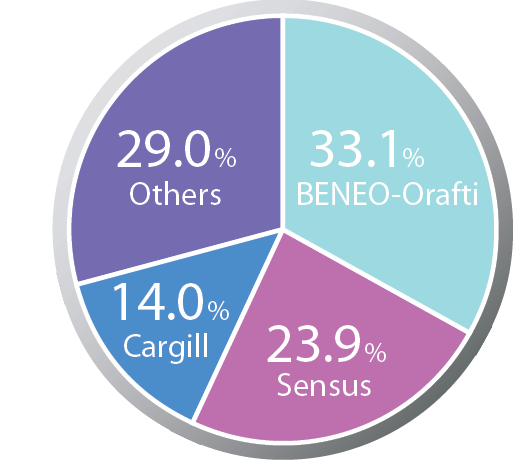

“The fiber market is growing in the U.S.” says Tonya Schoenfuss, assistant professor in the Department of Food Science and Nutrition at the University of Minnesota in St. Paul. “People are looking for ingredients to improve their health. Soluble fibers in particular are estimated to have a compound annual growth rate of 10 percent, and they’re actually quite expensive.” The prebiotics market in 2014 is $195 million and is estimated to grow to $219 million by 2020.

Focus on lactose

The technology is particularly exciting because it produces an indigestible fiber from a disaccharide milk sugar and creates a potential value-added ingredient from a relatively low-value milk processing coproduct, lactose.

Whey is the liquid leftover from making cheese and some types of yogurt. Once used largely for animal feed, whey protein is now sought after as a high-value, nutritional ingredient for human consumption. Concentrated whey proteins are often consumed by athletes to help build or repair muscle, used in infant formulas and by aging adults to help ensure proper nutrition.

Whey is concentrated by filtering it with water through a series of columns or membranes. As the whey protein is concentrated, other components such as fat, minerals and lactose permeate through the membrane. Schoenfuss’s research could open new doors that would change the value of that lactose.

“We’ve been looking at whey ingredients, trying to improve the value of the components we get out of milk,” Schoenfuss says. “We’ve been doing a lot with protein, so lactose seems like a good area to investigate for adding value.”

“Lactose from whey or permeate is an underutilized product due to its abundant supply in the dairy industry,” adds Donna O’Connor, AURI food and nutrition scientist.

O’Connor says the dairy industry produces several million tons of lactose each year. Lactose makes up about 4 to 5 percent of milk by weight. “There is a tremendous opportunity to use lactose in food applications and transform it from a commodity ingredient to a value-added product.”

An innovative approach

Schoenfuss’s research involved blending lactose with glucose and citric acid, then running the mixture through a twin screw extruder in a process called “reactive extrusion.” What went in as a white powder comes out of the hot extruder a stringy, caramel-like product. Once it cools, it hardens to resemble glass. It contains 40 to 60 percent fiber that can be easily ground and added as an ingredient to enhance the dietary fiber content of food or beverages.

“This work is aimed at bringing value and benefit to humans by developing a new functional ingredient for food use from an underutilized coproduct stream,” adds Mary Wilcox, vice president of business development for the Midwest Dairy Association, which oversees investments made by 10 Midwestern state dairy checkoffs. “Whey and its components increase the overall value of each pound of milk for both farmers and processors.”

Minnesota is the seventh largest dairy producing state in the country, with about 465,000 head of milk cows. Annual milk production is over 9 billion pounds. Processors in the state produce more than 600 million pounds of cheese each year, so adding value to whey components could have substantial impact.

“Dairy is unique in that it’s perishable and must be processed quickly,” Wilcox says. “Anytime you separate or concentrate milk, cheese or whey, another coproduct is created that must be dealt with. Since demand remains strong, both domestically and globally, for higher protein foods containing whey protein ingredients, the manufacturing and supply of permeate coproducts will continue to grow.”

“What Dr. Schoenfuss’s research has done is identify a straightforward, less expensive process for creating a functional dietary fiber that is in high demand,” says Rod Larkins, senior director of science and technology for AURI. “This is a classic example of using science to add value to a coproduct that could add profitability to the dairy industry.”

Prebiotic potential

Prebiotic fibers are a rapidly growing ingredient category for formulating food and beverages. Total fiber market revenue in the United States alone is projected to grow from $285 million in 2012 to over $512 million by 2017. Most oligosaccharides are extracted from natural sources, like inulin from chicory root. Capturing some of that fiber market by further processing lactose is an encouraging opportunity.

“It has a very high potential,” Schoenfuss adds. “It just needs to go through the basic food safety and regulatory requirements that all new food ingredients go through. We also need to test that it does provide a benefit to our digestive health when consumed. That is the next step—to determine if it is a prebiotic fiber.”

While the initial results of the university research are promising, more work is necessary to determine if polylactose really does constitute a prebiotic fiber. Polylactose would need to go through the FDA regulatory approval process to be accepted as either a food additive or as a self-affirmed Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS) fiber ingredient such as inulin before it can be added to the food supply.

“Once polylactose has been successfully proven to be a prebiotic oligosaccharide fiber in human studies, this work would help transform a dairy coproduct into a value-added ingredient,” O’Connor says. “It could be well on its way for expanded use as a fiber source in food formulations once regulatory status is achieved.”